Friday 8 September 2023 8 AM GMT (*Ghana time*)

I called my friend Dela who enthusiastically accepted an invitation to provide his most personal interview yet for adjoainghana.

Adjoa: So I'm very honoured to have you as the first guest interview for adjoainghana. And it's really special because we're also friends. So I feel that we're going to get into a lot of great conversation, and I would love for you to start by telling us who is Dela?

Dela: Dela is an artist born in Ghana. I am trying to understand my identity and am connecting this to my work through the use of materials rooted in Ghana.

Dela’s name means ‘saviour’ in the Ewe language of Ghana. Dela is part Ewe and part Ga, two distinct ethnic groups of Ghana. I asked Dela to tell us something interesting or unique about the Ewe people in particular.

As well as having their own unique style of art, this is what Dela had to say …

Dela: We are very spiritual. I think that is one of the biggest highlights. I think this shows in the names. All our names have some ties to the spiritual, like mine. And we have our poetry. I’m still exploring that side.

Dela was less exposed to his Ewe side growing up, but he is trying to understand more along the way. Including the language.

Dela: The last time I actually visited my “hometown hometown” was, um, 2001. That’s when my Grandpa passed. Any recollections like childhood memories was just usually family going there and, you know, having a good time. So I guess I didn’t really experience a lot of what someone would say, all of what the [Ewe] people encompass, like, you know the festivals …

Dela recalled the time he spent in his younger years on vacation in the Volta region of Ghana …

Dela: … We would just go and walk around the farm, which actually is part of what influenced me [with my art].

Dela spoke about how he saw beauty in the rustic materials lying around the farm, as well as the inspiration he drew from the aesthetic of charcoal and wood which his Grandmother sold in Accra.

Adjoa: I know you attended Achimota High School. What was that like?

Dela: I feel like that is the only school that I can actually say I’m so proud of and that I feel actually shaped me. The school was beautiful because it was antique (built in the colonial era) ... it had a lot of old stuff in the labs. I would see all these weird science devices and all those old, old things were really beautiful to me. I don’t know why I’m attracted to old stuff. I was a science student and spent a lot of time in the science lab.

Dela spoke about how he wanted to study art during school, but he was told to do agric science. He said that in a beautiful way, the experience shaped him because he was exposed to the science side. Overall, his experience at Achimota was one of getting to know himself and shaping the things to come.

Adjoa: So what would you then say are some of the formative lessons that your experience at Achimota taught you?

Dela: … That was my entryway into being creative … I feel like it really helped with [my] curiosity because you’re going everywhere in the school, sometimes breaking boundaries … it’s this idea of nurturing your curiosity … I feel like creativity is like key and we always need to fuel it.

Dela remembered something his dad said to him. His dad was supposed to be a lawyer. His family didn’t want him to be a doctor which is what he wanted to be. But he made up his mind that he was going to do it and his parents allowed him to go to medical school.

Dela: … in the end, him being a doctor has really been a blessing to the whole family. So I was like, well … if I believe art is the way I need to believe it … so I feel like that thing he said was like a seed in my mind. Believe so much in what you want to do, even if other people don’t believe it.

Dela passionately affirmed that for him, art was something he realised he needed to do …

Dela: If I strongly believe in it, then I needed to find out how to make everything work.

The top of Dela’s face would disappear at times throughout the video interview.

Adjoa: Don’t forget about me seeing your eyes.

Dela: Wait. Yes, my eyes.

Adjoa: So you were born in Ghana. You live in Ghana and a lot of people have left Ghana in search of opportunities elsewhere …

Dela: Greener pastures.

Adjoa: Yes, greener pastures. So what made you stay?

Dela: … A lot of the visual and aesthetic designs I use are right here.

Dela described the inspiration he draws from dilapidated buildings such as those in the vibrant Jamestown, observing how the paint peels and transitions from shades of green into brown. He drew comparisons to the abstract expressionism in the work of artists like Basquiat.

Dela: … So I started creating works based on what I was seeing … I was like, I could be anywhere in the world, but [Ghana] is giving me the aesthetics I want, you know? … So that’s the first thing.

Dela then spoke about the practical challenges that can come with moving somewhere and starting from scratch and how with the digitisation of the world, it is possible to gain exposure from anywhere you are.

Dela: However, my work is evolving … so I’m not closed to ideas … I guess it’s just the fact that where I am in my career … I realised that I felt like I’m getting everything here and I’m doing everything here. Obviously, time changes and if I have to do something somewhere else and I have to be there, I’m not going to close my mind to the fact of having to be there, to work from there.

Dela also looked at moving elsewhere from the long-term perspective of where he would want to raise his future family …

Dela: … Africa is really like family oriented and everything. Like before taking any major decision, it’s just like thinking through all of those things.

I asked Dela about any tensions that may arise between those who decided to stay in Ghana and those who left. He recalled a conversation he had at one of his exhibitions …

Dela: [The person Dela was conversing with] spoke in Twi … [and to translate what the person said would be]:

“so with the work you are doing, can you eat, can you feed yourself?”

I’m like, dude, what kind of question is this? Because he is living in the US … I’m like yes, you are living in the US … it doesn’t really matter where you are … You can be in the US and you still don’t make an impact with art.

… Some come back feeling that they are better than others because you feel like okay, now I’ve gained some exposure and … my eyes are opened … it’s just all perspective, you know? No matter where you find yourself, I guess if you want to come back to Ghana, I guess you still have to see things from … not from the point of I'm better than these people now, but what lessons can I take from here and bring back here? … That’s one think about Kwame Nkrumah which I really admired. He left, studied outside, did a lot of things. Then when he came back, he did what he did in Ghana and transformed Ghana …

Adjoa: So for those who might not be familiar with your work, can you describe what themes your art engages with?

Dela: … the more I worked on what I was working on, the more I realised that two key themes were present … rebirth and identity.

Dela described the materials he uses in his work, including inner tubes from car tyres, motor tyres and bicycle tyres which are found at vulcanizer shops in Ghana, usually by the roadside.

Dela: … usually all these old inner tubes that have been taken out [of tyres] are just left scattered all around the place … and these things, as I came to realise caused a lot of environmental issues because … the inner tubes contain sulphur, which is poisonous, [containing] quantities of carbon, carbon monoxide and a lot of other chemicals. And when they are burned … toxins being released, it causes a lot of issues and it causes … lung disease and everything. I realised that slowly that I was tackling an environmental issue.

However, the environmental issue was not what first gave Dela his idea. Dela was originally drawn to the idea of using found objects in art, as African art does.

Dela: I love [how] … we create things using found objects and things that are functional [and] have some purpose.

… I realised that there was this environmental aspect to my work which I couldn’t ignore, you know, which was the fact that I was actually upcycling materials and giving them a new function and a new purpose and keep[ing] them from being burned or just littered in the environment. So that’s really become a huge focus of my work. And that’s the rebirth. It’s just like I’m giving this new life.

Speaking about the materials, Dela says …

Dela: They’ve been dumped, rejected, everything.

Dela then drew a comparison between the state of the tyres, inner tubes and the human experience …

Dela: People who feel [that they] have been rejected … dumped somewhere [with] no value in life. And the idea that you can actually go and see a master artist and be transformed … so that idea of being transformed and changed …

So this is a spiritual rebirth, which is, I say, being born again. I was seeing that as well with the tyres, you know, because people [see them and think],

“What is this? This is an inner tube?”

I’m like, yes, it is …

When people are transformed, you don’t recognise them, like the past. The past doesn’t matter anymore. Like, you can say [about the tyres and inner tubes] …

“I knew you, you used to be lying over there and doing that by the roadside”.

[But then they say]

“… but look at me now. I’m no longer worth coins … I’m no longer useless. I’m now worth a lot more … I’ve been transformed. I have value.”

Dela continues …

Dela: And to me, these are the conversations I like to have with my work … to let people see that no matter where they are in their lives, they have this worth in them that once they come to God … that worth can really come out. That worth can really show.

Moving to the second core theme of his work, Dela says …

Dela: … when you are reborn, you have a new identity. You are no longer the same. The so-and-so from the past. You are now a new person. You have a new name.

Dela made the connection to traditional naming ceremonies …

Dela: So that’s why I give my works names … you are born from scratch like a baby. It’s a naming ceremony … and also that’s part of my African identity as well [which I am] bringing into the work now.

Adjoa: Can you describe your art style?

Dela: So my style is … tapestry, right. I should break down the style. I borrow a lot from the world of fashion … my mum was a fashion designer and my grandmother and my great grandmother … I was always reading fashion books like; I love the idea of fashion. And when I started painting … I started painting tapestry … I loved the classical artists. So this idea of tapestry was always playing at the back of my mind … borrowing different weaving techniques was coming to my mind …

Also Avant Garde fashion, the idea of … like taking the thing apart and putting it together like this weird way of creating garments, you know, like just exploring different garment techniques so I can create one that looks like a torn material …

Dela has also incorporated colour into his work through painting jute.

Dela: So again, borrowing from Avant Garde fashion, borrowing from weaving techniques and a little abstract painting …

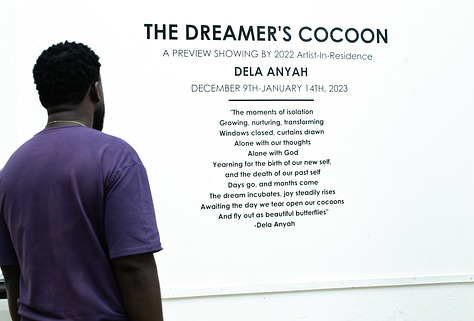

Adjoa: I want to take us a little bit into a different direction, but still on the theme of your artwork. So I met you at your first solo exhibition, I believe ‘The Dreamers Cocoon’. It was a chance meeting … I didn’t actually know that your exhibition was going to be showing. And the themes of your exhibition spoke exactly to what I was experiencing at the time, which was really rebirth, transformation and really looking at my identity within the Ghana context. And so can you tell us about a time where you yourself have gone through a rebirth?

Dela: … there are thousands of them. But … for the purposes of this interview I guess one of the biggest was starting with this work. So I was in a very, very dark space … I was really down.

… I was doing a lot of things. I was painting, I was creating bags, I was doing graphic design websites. What wasn’t I doing? So many other things … I started an NGO, was managing different Instagram pages for different types of things I was trying to work on, and it just felt like at that point everything wasn’t working … [I thought] –

“my life needs an upgrade. I need something to change.”

Dela had bought tyres and he had kept them lying around ....

Dela: … I remember my nieces would cut them to make dolls out of them … I didn’t know what to do with the tubes.

Dela came across a challenge on Instagram focused on prayer and worshipping God ...

Dela: I just joined that challenge and one afternoon laying down I was just like “God, you know, please, [I just need this one idea] so that I can just focus. Because at this point, it seems like everything is just haywire …”

Dela describes this memory as if it were fresh, recollecting how he then had this dream where he had seen the tyres and tubes woven together …

Dela: I just jumped out of bed and ran to the studio and I tried doing something with it and it took me hours. [When I had finished] my thought was like,

“doesn’t look too good … let me see. How do I even hang it?”

Dela was facing some urgency to produce something and he remembers thinking …

Dela: So, like, if God has told me that I’m doing this one thing, which is like, you know, tubes … then it has to work.

Dela recalled that he and his assistants continued from what he began with the tyres and tubes and they liked it …

Dela: It was like, the thing looks good … it works. I think my mum was like

“why does it look like a dress? It looks interesting.”

And when she said that I was like okay my fashion reference is working. Now it’s like … I’ve been transformed from [being] confused, all over the place to focused. And I feel like that’s my new identity.

But Dela added …

Dela: to say I wasn’t stressed; I’ll be lying to you. Everyone could see on my face. I would go to the studio and my face would just show that I’m stressed, I’m tired.

The connection dropped out for a little while but then it came back …

Dela: … I had like one month to make it work … I was going to be known as the guy doing work with tyres, no longer the designer [who] did this and this … this was a huge bet. So I created the first [piece] and I put that one on Instagram … I lost some followers … but it was this idea of when you are reborn or you have this rebirth, you need to stick to the [new] identity … so to me, it was like just putting it out there, like, okay, I’m now being bold in this new journey I’m taking. And if I believe that God told me to do it, I have to be bold about it.

Dela was signed onto the esteemed Noldor Residency and Fellowship Programme. The program, founded in November 2020, “is Ghana’s first independent artist residency and fellowship program for contemporary African artists on the continent and in the diaspora.”1 The program, hosted every year in Accra was founded by Joseph Awuah-Darko, “[a]n African contemporary art connoisseur, collector and thought leader,” to provide a dedicated studio space, community and platform for emerging African artists.2

Dela: So that’s the biggest rebirth … I feel like everything changed in me. I took that decision to be this artist that I am.

Adjoa: Your work has been exhibited and shown in galleries in Ghana and also internationally, Denmark, New York ... You have had your own solo exhibitions. You were also the recipient of the 2nd Runner-up prize for the 2022 Kuenyehia Prize for Contemporary Art. You have attained success with your work. What are the challenges behind this story of success for you to get where you are now?

Dela: … the biggest challenge is mental. Like just believing that it will work, you know, because it’s different …

Dela freely shared about his faith in God and gave God the credit for his ideas …

Dela: … I feel like it’s just … believing, you know? The space of not being anxious, trusting God. It’s like if you told me to do this thing, it’s going to work … patience. Having patience that this is going to happen … just hav[ing] faith. So I think there’s a lot of lessons that I’ve had to learn …

Dela reflected upon his second solo exhibition ‘Elementary Rebirth’ hosted at the Nubuke Foundation …

Dela: [During the exhibition] I had to go there numerous times to meet new people and that trained me on how to talk about my work because you have schools coming and kids come to ask you a question … people come in groups and I have to talk about the work. So it gave me this platform to do that.

Adjoa: I was doing my research into the inner tubes … I read somewhere (this could have been in another interview or through your glossary) about how the inner tubes are what gives a car or bicycle their structural stability and suspension. And I wanted to ask you in your life, what have been the stabilising factors that have grounded you and given you a strong foundation?

Dela: I’ll say God … I always learned to go back to God because I feel like, okay God, you gave me this talent. I don’t know why. I mean, it’s the one thing that I have. I don’t know why you gave it to me. So you have to tell me what I’m doing with it. So I feel like that’s always got me in the midst of everything. Like it’s always going back to God … because I constantly have to pray to know what I’m doing.

If you follow Dela on Instagram, you would have seen that he has been posting pop-up exhibitions as part of his latest project ‘Homecoming’. Displaying his works in situ, in their natural environment, by the roadside, at the vulcaniser workshops …

Adjoa: Can you tell us about Homecoming?

Dela: So I’m going to read something …

Where am I from? Who am I? What is my identity?

So [its] this idea of the tyres asking, “where am I from?” … because the tyres are in a studio that is new … they’re like art pieces, but the tyres are coming from different shops … it is a question of what is my identity? Where am I from? Because people see the works, but no one knows where they’re from.

In Dela’s eyes, the shops where the tyres were originally found, some dilapidated, are beautiful.

Dela: … So to me it was like… let’s go to the roots of where they are from, because I talk about it a lot, but no one really knows. And I feel like … the works … do they even know where they are from? They don’t know their roots, you know? So to me, it’s like a homecoming.

Dela references the song Wogb3 J3k3, a Ga term meaning “we have come from far”.

Dela: … [this] song comes to mind when I imagine the Homecoming series … I was thinking about how they have come from distant lands. How does people seeing where the tyres come from, affect how they now perceive the work?

Dela also spoke about the interactions he has had with the vulcanizers that he acquires the tyres and tubes from. And how that is also an exploration of rebirth and identity …

Dela: So the Homecoming series was also [about letting the vulcanizers see what I have been using the works for]. Because … whenever I go there, the first question they ask me is like,

“What am I going to use this thing for?”

And sometimes they ask in a very insulting way … like

“don’t you have anything better to do with your life?” things like that, you know.

… I guess … I realised also … people should have that conversation on their identity …

Dela speaks about the Black Lives Matter movement and how it connected with his works, although this is something he hasn’t really shared a lot on …

Dela: 2020 [when we saw the Black Lives Matter movement come to the fore] was when I actually started sketching these works.

I didn’t want to emphasise on that too much, but it’s interesting how it all comes back again to identity … the Black identity … Yes, I’m now in a distant land … but then my DNA [is] what makes me who I am.

Talking about the tyres, Dela continues …

Dela: …. you [the tyres and tubes] came from someplace … now we go there [the vulcanizer workshops] and you see this [art piece being displayed] … so there’s this bigger conversation taking place, which I want people to have as well whilst also interacting … with the exhibitions I’m doing …

I’m engaging with the vulcanizers who are now seeing the works and are surprised … you know, they are really surprised.

Dela observes how some of the vulcanizers have increased the prices at which they sell him the tyres and tubes.

We pause the interview as Dela’s niece made a guest appearance.

Adjoa: Who is a vulcaniser? Can you describe them and why they’re important to your artistic process?

Dela: … the word vulcaniser comes from vulcanisation. That is the process of adding sulphur to rubber to make it stronger and adding other properties … [a vulcaniser] is a skilled worker. And also those people in Ghana who fix tyres as well. When there is a puncture, they patch it up. If you want to replace your tyre, they do it for you. Everything that has to do with tyres. They are the ones responsible for that … so they are all around … every place you can imagine. Every community I think has more than one.

Adjoa: One of the terms that I got from your glossary that I wanted you to expand upon is this term Afrobutylism. It’s a niche art form that you coined. So that’s why I’ve never heard this word. So can you tell us about this term?

Dela: Afro comes from Africa … the inner tubes are made out of butyl rubber … my core material … so that’s the reason why I use the butyl in there, because of the focus on the butyl.

Dela notes that the butyl also signifies how he is upcycling the tyres and tubes, transforming them and using them to create art pieces that are tackling issues. Dela continues …

Dela: There is the ‘ism’ side. Usually most art movements have this.

Speaking to the Afro part of this terminology, Dela says …

Dela: … I knew I could use the techniques I learned from Africans using found objects to create their work [and I apply] that to the inner tubes to create works. So that’s kind of how I saw the [Afrobutylism] coming together.

Dela is expanding his glossary to include more unique terms that reflect the expansion of his practice - adding the term Tire-verse.

Adjoa: I think what’s really unique about your work is how you really emphasise on this message of using discarded objects and upcycling them. And so just briefly, what are some ways in your own life that you have upcycled?

Dela: Wow. This is the first time I’ve received a question like this. This is really interesting … I guess maybe I could take my personality right … and how I took what seemed to me like it wasn’t where I had to be and upgraded it, add value to it. I went through this season of realising that you need to add more value to yourself. Like you need to see yourself in this new light … I was like …

“this is the new Dela.”

I am no longer the old Dela. The old things I used to do, the old way I used to dress, the old things I wanted.

And so I wrote a long list of who I felt I should be … and started living according to the new list. If you perceive yourself as someone who is not worthy of certain things, you also receive that. If you see yourself as being worthy of certain things, you also receive that. So you know that, okay, I’m worthy of this. This is what I deserve in my life, that’s what I need in my life. And I shouldn’t package myself in a way that will get [me] what I don’t want.

Dela has done branding and marketing and spoke about this idea of creating a brand guide for your life …

Dela: … you have your guide like this is who I am and it’s like a script … so I had to just … work on that script. And ever since I did that, it’s just been interesting … and when I see something slacking it’s like hey, let me just go back to that script.

Don’t settle … realising that, no, I know what I want and I’m going to get what I want … so having clarity of perspective of what I want I guess.

And on people reminding you of the old you, Dela gave us a great line to use …

Dela: … that address has changed. It’s no longer available.

Adjoa: So to get it correct, the way you’ve upcycled your life, you became clear on a new way that you wanted to be in the world and approach your life and you started acting in accordance with that and a big part of that was your mindset, your mindset shift of believing that you were worthy of the standards that you set for yourself and not settling?

Dela: Yeah, exactly, exactly. Because this is like taking the old and making it new.

Adjoa: We’re getting to the end of the interview and something that I wanted to ask you … and I really got excited about this … So you know how your name has the connection to saviour? And we know that you’re a man of faith … how does it feel to be a saviour of these discarded objects? Because what you are doing is you are saving discarded objects, you’re giving them another life, you are giving them another chance. Like you said, they take on a name, they take on a new identity. Have you ever thought of that and about how that makes you feel?

Dela: Well I’ve never thought about that … only God gets the glory … [I] am not even trying to imagine me putting myself in the same boat if you know what I’m saying … I guess I’ve never thought of myself as a tyre saviour, you know, like, “I’m saving the lost tyres …”

We both laughed …

Adjoa: saving the lost tyres, that’s a good one.

Dela: … I just haven’t made that connection, it’s funny at the same time, I just haven’t made that connection.

Adjoa: Then I wanted to ask you, do you see yourself as an activist or do you see your work as activist in any way?

Dela: I feel like when I began my art, it was all about activism … when I started working in upcycling discarded materials … I always find myself as an activist because as much as I was also working with these materials, I also touched on other issues in society as well. So I guess that's always been part of me ... want[ing] to see something good in the world. I’ve done a lot of charitable activism type of work … so there’s that underlying desire to make some change in the world … I guess [my art] helps me to be able to do that too.

Regarding the environmental aspect of his art …

Dela: … I’m not coming from a point of having all the answers … This is the part I’m tackling. I have seen this rubbish and I’m giving the rubbish a new life. That is what I am doing … and that’s the role I’m playing … I’m not tackling everything …. I can’t pick up every single tyre in Ghana for my work …

Adjoa: I think you answered that very well and I think that really clarified the messaging behind your work. And I think that it's important to not project the burdens and solutions of the whole world onto one person and one cause.

But I actually was even thinking your work in itself, the message of what your work represents … to me, it's very activist, just in the sense of … I feel that art (I'm not sure, I'm not going to generalize) but I do think that people you know … there's this whole thing about aesthetics and a lot of aesthetics now are things that look “clean, neat and tidy”, things that can be easily, you know, neatly put up and sort of, you know, very … I would say like easily digestible. They don't always force you to confront some of the less appealing themes or ideas.

And I think that your work is really important in bringing that message to light in a way that I think, yeah … just even this whole Homecoming project is activist in itself because a lot of the time (this is another thing about identity) … sometimes we forget about where we come from.

We go on to attain success. We become this “new clean version” and then, you know, that's it. We kind of lose the strength of our message. But I feel like your work, even though the pieces are really repurposed and upcycled, the fact that they're now going back and being presented in their original places is quite activist to me because it shows that value comes from those places and that can never be erased.

So I think that for me that's sort of like some of the ideas I thought about your work.

… if you were just thinking about speaking to the adjoainghana community, where do you think are some of the places in our own lives and environments that we disregard and overlook?

Dela: Wow. Um I would say our ideas … people could make a huge impact in the world if they just saw value in their ideas and didn’t just disregard them … Because God is putting ideas in our hearts and our minds every day on who we really are. Usually we always settle for second best, for [what] someone says we should be … But then it’s never really about what God is telling us to be or what we should do.

Because God’s path is usually, at the beginning, [one where] you don’t have answers … but then there’s always gold at the end of the rainbow … there’s always something beautiful there. So yeah, I’ll say our ideas.

Adjoa: Wow. I wasn't expecting that answer. And I think it's a really good one and I think that you have given us some homework, some encouraging food for thought. I want to ask you, what is something you would not have learned or experienced had it not been for your art?

Dela: Um. Patience and focus … these things are always internal things. And it’s less to do with externals … it all goes back to things we have to change on the inside …

Dela quotes the book of James in the Bible, James Chapter 1 verse 8:

A double minded man is unstable in all his ways.

… you’re not sure what you are doing in one area … because if you’re not sure about what you are doing career wise, the next it moves to who you want to be with … then it goes to where you want to be in your life, where you want to live … what you want to eat today …

But if you start focusing on one thing, “I know what I want here”, “I know what I want” … I love [how] things fall into place and align with it … I had to stop the idea of being double minded … [I learned] how to focus on one thing … I think [that] is the one thing that I learned. I’m still working on it, but it’s the one thing I learned.

Adjoa: … I like how you talked about the internal … And that's really powerful because I think it reminds us that a lot of what we're looking for externally, it's never going to be as valuable and transformative as the internal lessons and growth. And finally, I just want you to tell us what you would say to someone reading this interview who is struggling to see their value?

Dela: … Kind of like the same thing that I did … I guess just to ask who they are and what they need to do because it all begins there. Like clarity on who am I? Having that answer begins to unpack the rest. As long as you know who you are … No, I can’t be with these people. I can’t be tolerating this … But then if you don’t know who you are [it] becomes very difficult … Because who we are or who we think we are is who we attract to ourselves.

… because then we know who we don’t need in our lives. Then we know, okay fine, all these things that I’ve probably built up in my life. I need to let them go and start afresh … and I feel like God brings all the people we need … who help affirm the value that we have.

Adjoa: … it sounds like in what you're saying, we kind of need to look to something greater that will give us a purpose that goes beyond the validation that we're seeking through things. And like you said, when you have that shift, you were saying how the world starts reflecting back to you those better beliefs that you have about yourself. So I think that is powerful.

Dela: … it’s kind of like self-reflection or introspection. [Ask yourself], “so what are the things people have said to me that they have seen value in that I have rejected or am quick to say no to?”

… I like to encourage … I guess it’s because of the journey I’ve been on … and the key thing I realise is that people reject encouragement … So I guess the one thing I tell people to do is to be sensitive to every comment that comes … just check your reaction to the comments [and ask yourself], “am I fighting progress in [my] life because I don’t believe that I’m worthy or I’m good enough?”

… Many times people don’t even see what they have. And sometimes its draining in the sense that you are seeing that this person is so good, so great and they are just speaking so much negativity into their own lives.

… in this world you have to be hungry and realise that a shift needs to happen … giving unsolicited advice doesn’t work … but when you are ready for advice and people give it to you, I feel like it [goes] deeper, you know? And I just really feel like if a lot of people start rejecting all the [negative] things that they've believed about themselves, like things could change … a lot of things could change. The mind is so powerful.

Adjoa: That is a great way to bring the interview to an end. But I wanted to just give you an opportunity to say … is there anything else that you'd like to add? And also, where can we find you?

We spoke for 2 + hours! And so we were trying to wrap it up …

Dela: I’ll say medaase … well, I guess my website is the first place delaanyah.com.

I really love what you are doing … especially the focus on … empowering people … follow adjoainghana!

Adjoa: thank you Dela. Is there anything else that you want to say for the interview? Like anything, is there anything else? I just want to make sure you're happy …

Dela: Oh, yeah, like I am. I guess this has been the most personal interview I've had … I thank you for helping me share the stories on this platform.

Adjoa: I'm very honoured that you are our first interview for adjoainghana. God, please help me with the technology [we had been experiencing multiple technical issues] … But I'm really excited to share your story and to share what you've shared. I'm really excited.

.

Interview by Adjoa for adjoainghana.

DELA’S WEBSITE

DELA’S INSTAGRAM

WATCH BEHIND THE SCENES

LEARN MORE ABOUT THE TIRE-VERSE

Institute Museum of Ghana. (2020). About Institute Museum of Ghana https://noldorresidency.com/about-noldor/

Institute Museum of Ghana. (2020). Leadership https://noldorresidency.com/367-2/

Thank you for the interview Adjoa ✨✨💫. Honored to be here 🙏🏽.